To ensure fiscal discipline, the government at all levels must be made to face financial consequences of their decisions." That is a quote from Anwar Shah’s paper, ‘Balance, Accountability, and Responsiveness: Lessons about Decentralization’. Dispensations in some states may not have read it. Following the footsteps of Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, the Punjab government too has given in-principle approval to restore the old pension scheme for its employees. Far from providing a compelling indictment of the new pension scheme, the move backtracks on one of the crucial reforms that helped state governments dodge a ‘fiscal bullet’. But how is it possible for states with two of India’s highest debt-to-GDP levels to take such fiscally profligate actions?

To ensure fiscal discipline, the government at all levels must be made to face financial consequences of their decisions." That is a quote from Anwar Shah's paper, 'Balance, Accountability, and Responsiveness: Lessons about Decentralization'. Dispensations in some states may not have read it. Following the footsteps of Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, the Punjab government too has given in-principle approval to restore the old pension scheme for its employees. Far from providing a compelling indictment of the new pension scheme, the move backtracks on one of the crucial reforms that helped state governments dodge a 'fiscal bullet'. But how is it possible for states with two of India's highest debt-to-GDP levels to take such fiscally profligate actions?

At the heart of such fiscal profligacy by states lies the transfer system, which is supposed to address a problem of imbalance between revenue and expenditure powers. However, sometimes, it also incentivizes a "raiding of the fiscal commons". From the equity perspective, the conceptualization of fiscal devolution is a pragmatic idea. It aims to correct spatial imbalances to ensure the economic stability of the Union. It aids states that cannot raise sufficient revenue on account of historical and geographical limitations. Similar frameworks exist elsewhere in the world, by which a federal government undertakes a balancing role in allocating resources. This is inevitable as substantive revenues are mobilized from a handful of urban agglomerates.

However, nearly half of the weight in India's devolution formula is income distance: i.e., the distance of a state's per capita GSDP from the state with the highest per capita GSDP. This can lead to cases of perverse incentives, wherein some states over-rely on these devolutions. This, however, is essentially inversely linked to a state's economic performance. As per the state budgets for 2022-23, of the total revenue receipts for states, the share expected from the Centre (sum of tax devolution and grants) ranges from 76% in Bihar and 57% in West Bengal to 47% in Andhra Pradesh and Punjab and 27% in Gujarat. Under-reliance on the state's own tax resources might partly explain how Bihar prohibited the sale of alcohol, a significant tax source for most states, without affecting its fiscal health or sustainability.

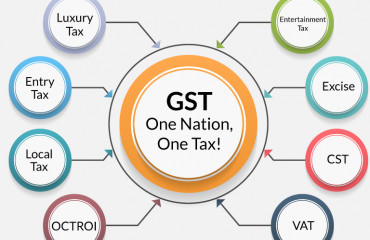

For a state, the primary source of budgetary resources is tax revenue (the predominant part being state GST) and the devolution of 41% of the general pool of taxes. The current paradigm has resulted in a situation where a substantive portion of the state's budget is an apportionment from the Union government, even while a high threshold of growth was guaranteed for the largest tax component in the state list (GST, i.e.).

To get states on board for the GST regime, financial assurance was provided to them by a 'Protected Revenue' clause. The Union government guarantees the minimum threshold revenue (compounding at 14% of 2015-16 levels) annually at a uniform rate, irrespective of the individual state's economic performance. It has resulted in a scenario wherein the state's largest tax head (SGST) is divorced from the prevailing economic environment in the state. The effects, though unintended, were glaringly visible when states were given the autonomy to decide on lockdowns/mobility restrictions during the last waves of the covid pandemic. Barring a few notable exceptions, there were hardly any attempts by states to balance the economic repercussions and extended lockdowns became the norm.

Protected revenue and high devolutions have disincentivized the states to carry out reforms. This is where a competitiveness framework comes in. As M. Govind Rao puts it, "Competition motivates innovations and productivity increases."

A productivity-based competitiveness definition by Michael Porter sees competitiveness through the lens of a place's productivity level. Productivity drives the standard of living for individuals there. Healthy competition between Indian states for investments, incentivizing political innovation and development, is thus very critical. This would result in an overall conducive economic environment by fostering competition among states, thereby contributing to higher aggregate growth.

Adopting a competitiveness framework warrants that transfers to a state and its fiscal resources in general be linked to its economic performance. Currently, this link is broken, as an incentive mechanism at the level of the state exchequer is delinked from the state's GSDP performance. States will have to be incentivized to compete. Such a system would incentivize efforts undertaken by state governments to raise revenues and also improve the quality of public expenditure.

The growth of India is nothing but the growth of its constituent states. The link between a state's economic performance and its budgetary resources must be revitalized. This economic incentivization of reforms is critical to the long-term fiscal health of both the Union and states. Abhijit Sen, one of the dissenting members of the 14th Finance Commission, pointed towards the pitfalls of a drastic increase in tax devolution that is unconditional. Going forward, we should ensure an increased share of conditional transfers (possibly at least 5% of the divisible pool) based on reforms, quality of expenditure and fiscal sustainability in place of the current regime. Only then can we ensure that state governments face the financial consequences of their fiscal misadventures.

These are the authors' personal views.

Aditya Sinha & Chirag Dudani are, respectively, additional private secretary (research) and assistant consultant, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister